Moving us into heightened states of observation and bringing attention to everyday narratives, as well as wider historical implications, the works in the exhibition ‘Still Life Now’ and accompanying ‘Still Lives’ film program consider how contemporary artists and filmmakers draw on the ideas of the still-life tradition to explore issues of consumerism, beauty, power, postcolonialism and gender politics.

When we think of a picture created in the still‑life tradition, the image that comes to mind might include freshly cut flowers, fruit and vegetables or manufactured objects, frozen in time. Captured in near-perfect detail, these artfully arranged inanimate objects appear to be examples of domesticity; in fact, they are often coded with symbolic references, the artists having used sumptuous imagery to reflect on nature, wealth, exploration and, importantly, mortality. Artists today continue to share, and reject, the concerns of traditional types of still life, such as the memento mori (the stoic visual reminder of the inevitability of death) and the vanitas still life (the use of elaborate spreads to highlight life’s transience) by using strategies of repetition, appropriation and transformation across media, from painting, printmaking and sculpture to performance and time-based works.

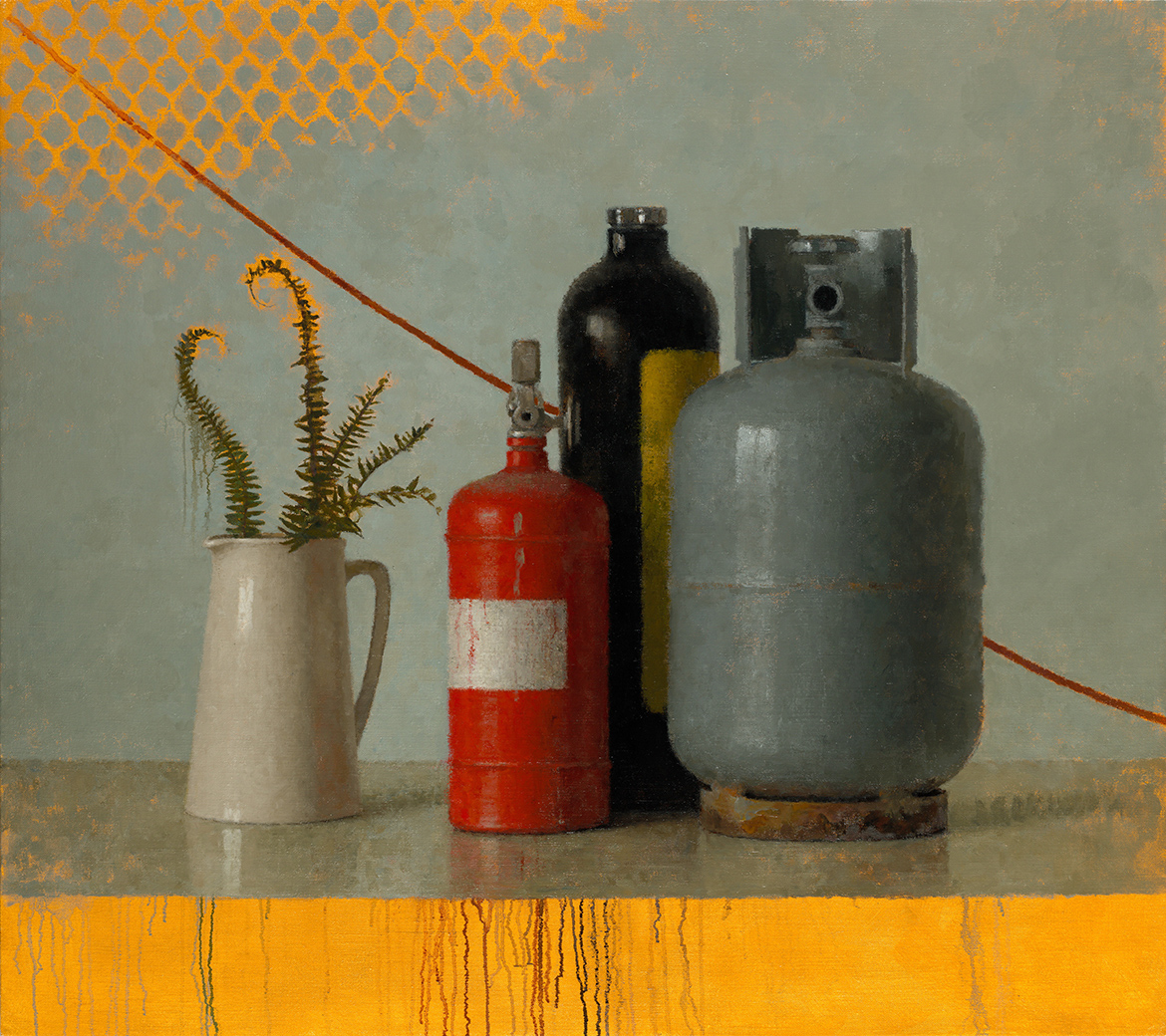

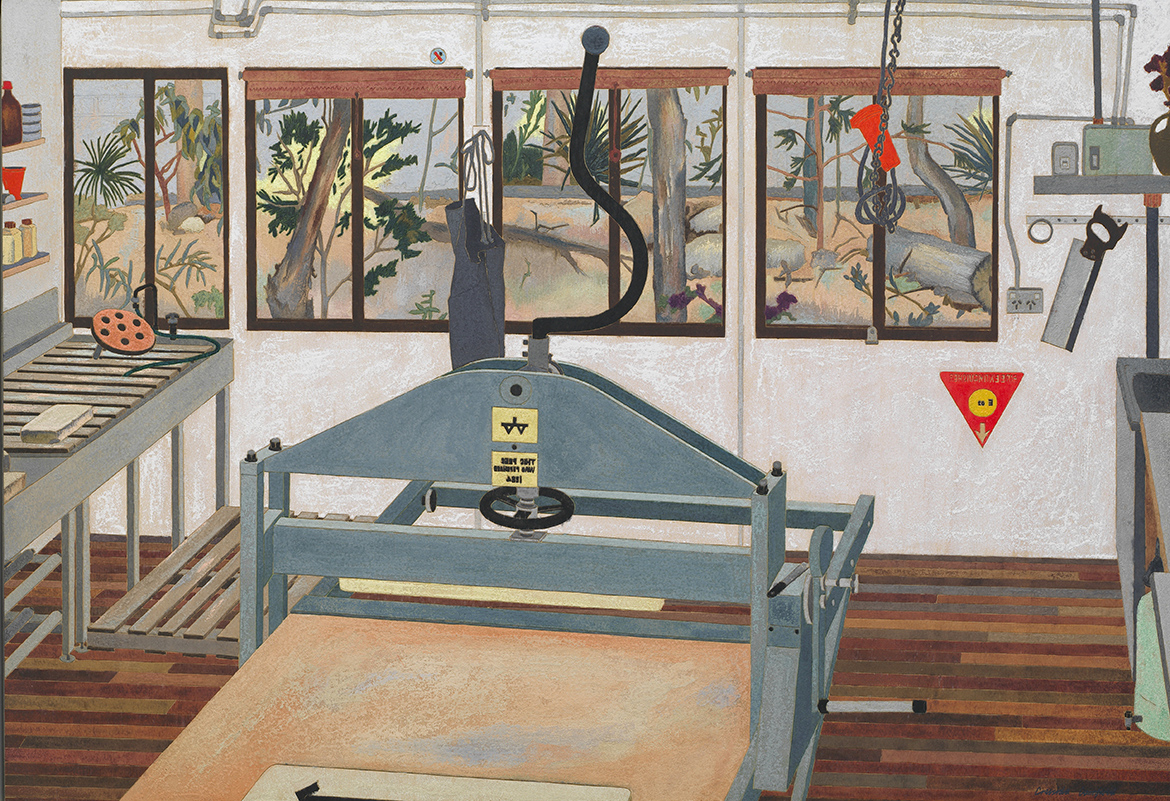

Contemporary artist Jude Rae disrupts the illusion of realism with SL447 2021 (illustrated) by adding small visual clues in the form of dripping paint marks and brightly coloured haloes. Conversely, Cressida Campbell’s carved woodblock painting The lithographic studio (Griffith University) 1986 (illustrated) transforms a busy print studio — an environment specifically created for the production and manufacture of images — into an image itself.

Jude Rae ‘SL447’

Cressida Campbell ‘The lithographic studio (Griffith University)’

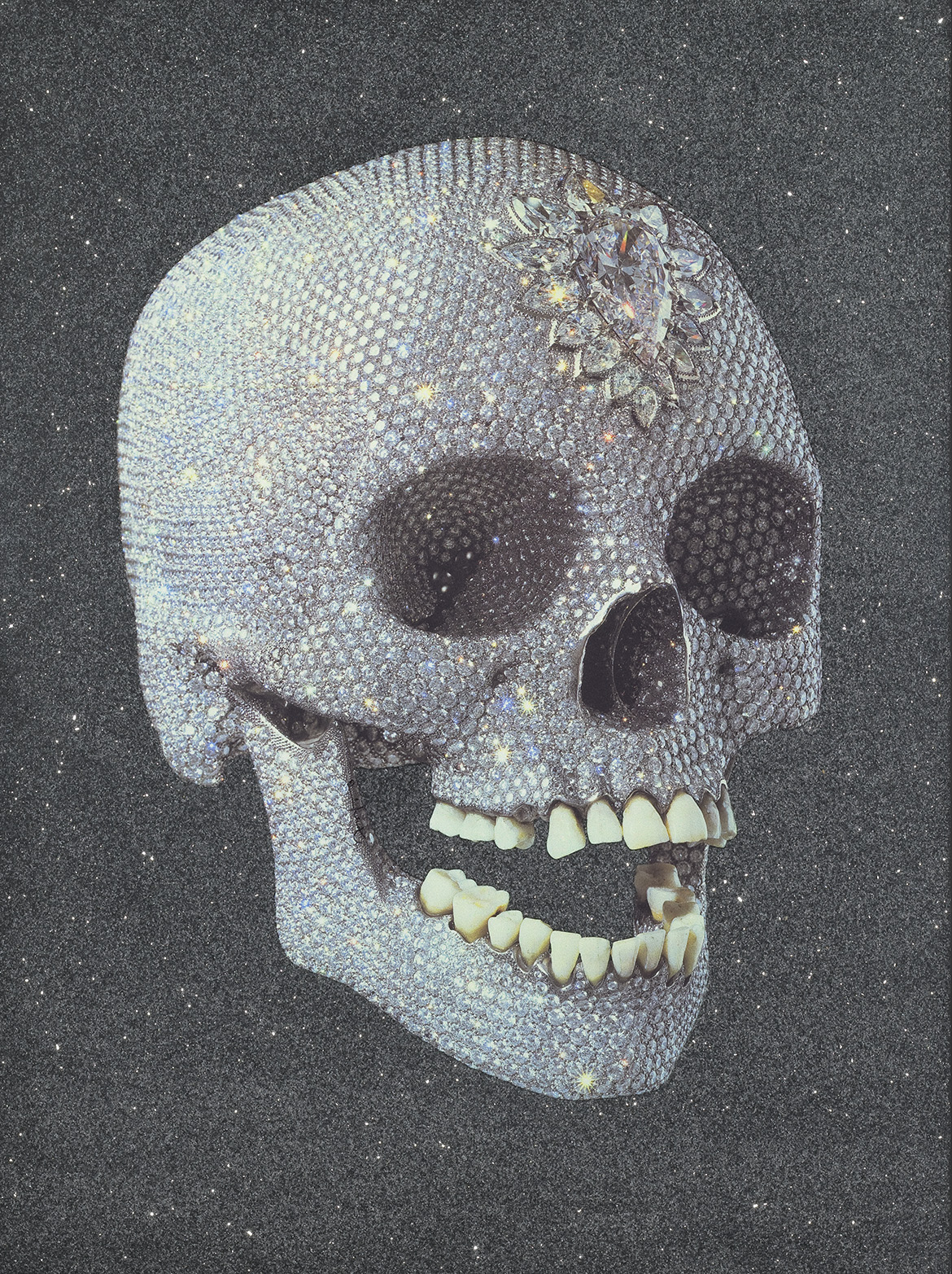

Reproduction and representation haunt the still life, almost as much as does its relationship to time. The genre’s popularisation in seventeenth-century Europe transformed image-making into a commodity, imbuing these pictures with heightened material value. Known for his audacious embrace of the art market, artist Damien Hirst plays on the currency of images to emphasise the futility of wealth: the print For the love of God, laugh 2007 (illustrated), of a real skull covered in over 8000 diamonds, and which is itself embellished with diamond dust, transforms this classic motif of death into a glittering object of desire.

Damien Hirst ‘For the love of God, laugh’

DELVE DEEPER: Damien Hirst’s ‘For the love of God, laugh’

Artists such as Michael Cook’s ‘Natures Mortes’ series (illustrated) and Salote Tawale, who reclaim historical imagery to consciously reflect on contemporary states of being, create new commentary through works that take the troubled colonial past of the still life and its relationship to trade as their subject. The featured works by Emily Kame Kngwarreye ( Yam dreaming 1995 illustrated) combine ancestral knowledge with rich painterly forms to explore intangible connections to food and Country. The strength of contemporary voices is similarly shown in the collaborative piece Carving Country 2019–21 by Brian Robinson and Tamika Grant-Iramu, who use the process of carving as a way of celebrating life and First Nations cultures through visual storytelling.

Michael Cook ‘Nature Morte (Agriculture)’

Emily Kame Kngwarreye ‘Yam dreaming’

DELVE DEEPER: Michael Cook’s ‘Natures Mortes’ series

The moving image can also use stillness to bring attention to the passing of time and the fragility of life. Accompanying the ‘Still Life Now’ exhibition is the ‘Still Lives’ cinema program, the selected films in which reflect many of the concerns of the genre on screen. ‘Slow cinema’ is style of filmmaking that uses long shots to create broad narratives that offer space for visual contemplation. Oxhide 2005, directed by Liu Jiayin, and Abbas Kiarostami’s final feature, 24 Frames 2017 (illustrated), each use structured static frames, reminiscent of still‑life imagery, to move us into a heightened state of observation and bring attention to the everyday narratives that unfurl through the experience of living. The darkly comedic films A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 2014 (illustrated) (director Roy Andersson) and Meanwhile on Earth 2020 (director Carl Olsson) feature suites of vignettes, presenting experiences of death that confront its macabre associations. The still-life tradition of displaying extravagant, excessive spreads of luscious foods is explored in Peter Strickland’s latest feature film, Flux Gourmet 2022 (illustrated), and in Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover 1989, both of which deploy visually lavish, gluttonous depictions of food, ultimately creating a sense of revulsion and disgust.

RELATED: ‘Still Lives’ film program

In the present, the still life is a space for creative experimentation. Consumerism, beauty, postcolonialism and gender politics are addressed through the contemporary still life, in both the gallery space and on screen, proving that life is anything but still.

Victoria Wareham is Assistant Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

’24 Frames’ Dir: Abbas Kiarostami

‘Flux Gourmet’ Dir: Peter Strickland

‘Still Life Now’ is in Gallery 2.1, GOMA, until 19 February 2023. The ‘Still Lives’ film program is screening at the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA, until 12 March 2023.

Featured image: Production still from A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 2014 / Dir: Roy Andersson / Image courtesy: Madman Entertainment

#QAGOMA

More Stories

That's a wrap for Art in Bloom 2023!

A Vortex of Hoplessness – Maniscalco Gallery

How Personal Stories and Backstories Enables Word-of-Mouth Marketing for Visual Artists